At a time when domesticity and what’s inside the home makes up the majority of what most people encounter in their daily lives, the still life is having a resurgence on social media – from influencers sharing their own photographs of satsumas and candles, to posting 18th-century paintings of shells and corals.

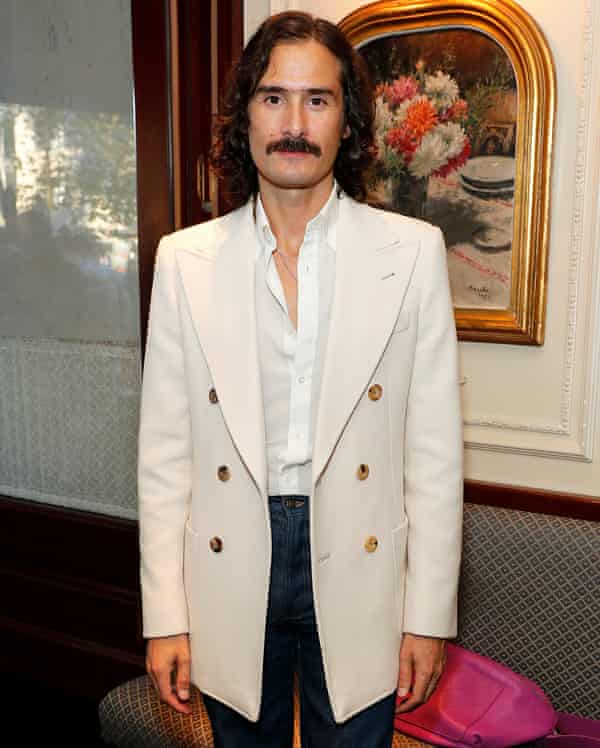

The still-life hashtag has more than six million Instagram posts. Lucy Williams, an influencer with more than 490,000 followers, has been posting shots of lamps and lemons throughout lockdown. Fashion industry insider Ben Cobb recently shared an 18th-century still life by French painter Anne Vallayer-Coster on his feed, while interior designer Luke Edward Hall has been posting shots of just-opening narcissi against books.

“One of our top-performing posts in the past 30 days is a still life painted by Rachel Ruysch,” says Abigail Tavener, social media manager at Sotheby’s London. Still lifes, she says, “can be counted among our best-performing content, with a handful of examples garnering more than 10,000 likes – double our average number of likes-per-post.”

A clutch of artists are also giving the still life contemporary currency on Instagram. Sydney-based painter Gabrielle Penfold came to still lifes in a very Instagram-first way, after being struck by the craze for everyone documenting their food. She started painting similar scenes: “I would put it on Instagram and people would respond really well.”

For her, this is what a still life is: “It’s something that resonates with people … nothing harsh to have hanging on your wall. It makes you feel happy – and, especially in these times, you want to feel good!”

Miriam Dema is another of the artists. “What I like the most about still-life paintings is that they are a reflection of a specific moment … and that they give value to everyday elements that would otherwise be lost in oblivion.”

Of course, not everyone has the luxury of being able to stay at home, but at a time when the domestic sphere makes up the majority of many people’s days, it also feels apt that a medium elevating the everyday – the literal bread and butter, or ephemera, of daily life – is finding fans. Hall has always enjoyed photographing bits and pieces at home but “because I’ve been spending much more time at home, I’ve naturally ended up taking more photographs in the house”.